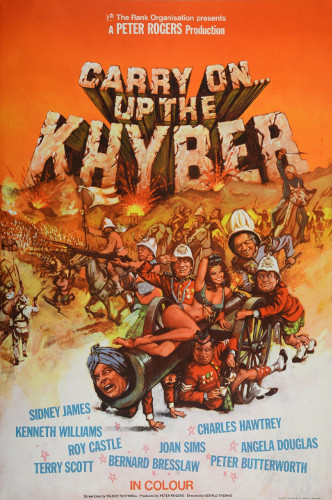

Director: Gerald Thomas

Writer: Talbot Rothwell

Stars: Sidney James, Kenneth Williams, Charles Hawtrey, Roy Castle, Joan Sims, Bernard Bresslaw, Peter Butterworth, Terry Scott, Angela Douglas and Cardew Robinson

It’s hard to explain to anyone not brought up in the UK just how much of an institution the

Carry On team were and still are, even if they haven’t made a movie since 1992 or a decent one since at least 1975. It’s especially hard to explain to Americans how they got away with that sort of material in the 1960s, when the Hays Office routinely stripped out dialogue that had to do with sex, but they even had Christmas specials on television in the UK. You see,

Carry On movies are a mixture of double entendre and dirty joke, the seaside postcard brought to life, and they’re a uniquely British thing, a descendant of the music hall. There were 30 original Carry On movies made, plus a 31st that’s new material wrapped around clips; there were also four Christmas specials, a thirteen episode TV show and three stage plays. All were produced by Peter Rogers and directed by Gerald Thomas. The majority were written by two writers: the first six by Norman Hudis and the next twenty by Talbot Rothwell, who would have been one hundred today.

How Rothwell got involved with the series almost sounds like the script for a

Carry On movie. He was a Royal Air Force pilot in the Second World War; after being shot down over Norway, he was imprisoned in Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe-run officer camp that was made famous by the films

The Wooden Horse and

The Great Escape. He started to write as a POW, for concerts that aimed to both keep up morale and drown out the noise of tunnel digging. He befriended actor Peter Butterworth in the camp and partnered on those concerts; he would later introduce him to the

Carry On series, in which he would become a regular, appearing in 16 of them. Rothwell wrote a spoof of this sort of thing,

Carry On Escaping, but it was never made. Having held ‘respectable’ jobs like town clerk and police officer before the war, he turned to writing as a career in the fifties, penning comedy sketches for TV shows featuring established comedians like Terry-Thomas, Arthur Askey and Ted Ray. His first feature film scripts were dotted around the mid-1950s. However, he didn’t write

Carry On Sergeant in 1958, or the next five films in what became a thematic series; Hudis did.

Carry On Sergeant was intended as a standalone film. It was adapted from a play by the historical novelist, R. F. Delderfield, and stars the first Doctor, William Hartnell, and Bob Monkhouse, so it’s hardly what the series became. If anything, it’s a 1958

Police Academy, merely with conscripts into National Service rather than policemen. However, the cast list did include Kenneth Williams, Charles Hawtrey, Kenneth Connor, Terry Scott and Hattie Jacques, who all became regulars in the

Carry On films that were spun out of this film’s success. The first four were still around for this sixteenth film in 1968; Jacques appeared in fourteen between 1958 and 1974 but not this one. At that time,

Carry On movies tended to throw respectable professions into a comedy framework, following quite closely the formula of the first, such as

Carry On Nurse,

Carry On Teacher and

Carry On Constable. However, they would soon begin to take on British institutions, traditions and tropes, especially after Rothwell replaced Hudis as the series writer.

While Rothwell wrote the eighth film on spec,

Carry On Jack, it was made after

Carry On Cabby, which he hadn’t written as a

Carry On film at all; he’d submitted it to Peter Rogers as a standalone picture,

Call Me a Cab. Rogers liked his work and brought him on for the series. To my mind, it took him a while to warm up,

Carry On Spying and

Carry On Cleo being overrated entries in the series, even if the latter did feature what has been voted the greatest one-liner in movie history, which Rothwell admittedly borrowed from the radio show,

Take It from Here. Kenneth Williams, portraying Julius Caesar, shouts out, ‘Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it in for me!’ To me, Rothwell hit his stride in 1966 with

Carry On Screaming!, a spoof of Hammer horror movies, because the next half dozen are great bawdy fun. Personal favourites of mine include

Carry On Henry (about Henry VIII’s wives),

Carry On Dick (about highwaymen) and

Carry On... Don’t Lose Your Head (about the French revolution).

While fans argue about which is the worst feature in the series (many vote for the last,

Carry On Columbus, released fourteen years after its predecessor to tie in to the 500th anniversary of Columbus reaching America, but I’d suggest either of the two that came before it,

Carry On England or

Carry On Emmannuelle), it’s almost universally agreed that

Carry On... Up the Khyber, is the best. In fact, the British Film Institute included it in their list of the 100 greatest British films, in 99th place just above

The Killing Fields. It’s hard to argue against it being the most quintessential, partly because it featured most of the series regulars in some of their best roles but partly because it focused around a subject that was ripe for ridicule in 1968: the colonial era of British expansion, in which we waltzed into other countries and proudly proclaimed that they were ours, and the Kipling-esque adventures that glorified it, like the 1939 version of Gunga Din. The time was right, the people were right and the end result was hilariously right.

We’re in India in 1895, with the British in charge but the natives restless. Her Majesty’s governor of Khalabar, in the northwest of the country bordering Afghanistan, is Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamond, in the form of the irrepressible Sidney James, so good at playing a dirty old man with an even dirtier laugh. His foil is Randy Lal, the Khasi of Khalabar, the local rajah, played by Kenneth Williams. It’s worth mentioning here that the humour is thoroughly English, to the degree that many jokes will fly over the heads of those from other countries. For instance, ‘khazi’ is military slang for a toilet and the film’s title, in addition to referencing a real location, is an example of Cockney rhyming slang, in which a word is obscured by shortening a phrase with which it rhymes. For instance, ‘use your loaf’ means ‘use your head’ because ‘head’ rhymes with ‘loaf of bread’. Of course, this is often used to obscure words not usable in polite company, such as ‘cobblers’ from ‘cobbler’s awls’ or ‘balls’ and, here, ‘Up the Khyber’ from ‘Khyber Pass’ or ‘arse’.

Rothwell defines the state of affairs perfectly at a polo match. The Khasi tells his daughter that Sir Sidney is the British governor, ‘whose benevolent rule and wise guidance we could well do without.’ Why does he smile at him so favourably? ‘Because in these days of British military supremacy, the Indian must be as a basket: with two faces.’ Meanwhile, Sir Sidney tells his wife, Lady Joan, that the Khasi would like to massacre him and ‘every other Britisher in India’. Why does he smile at him like that, then? ‘Because as a top-ranked British diplomacist, I’m as two-faced as he is.’ They do say that the best comedy is based in truth and there’s much truth here, not least in the final scene, in which the native Burpa tribe attacks the Governor’s Residence and, while the men fight outside, the Governor sits down to a black tie dinner, with orchestra, and everyone ignores the battle, even with the room being destroyed around them. This is the most ridiculous yet still truest example of ‘stiff upper lip’ that has ever been filmed.

But how do we get there? Well, Sir Sidney’s province is defended by the 3rd Foot and Mouth Regiment, colloquially known as ‘the Devils in Skirts’ because they are said to wear nothing under their kilts. Rothwell suggests that this is the primary reason why the natives have not revolted. In the words of the Khasi: ‘Think how frightening it would be to have such a man charging at you with his skirts flying in the air and flashing his great big bayonet at you!’ But the local warlord Bungdit Din, surely the best role for the 6’ 7” Bernard Bresslaw in 14

Carry On movies, flashes his scimitar at the cowardly Private Widdle who promptly faints at the sight. Because it’s so important, he looks under the man’s kilt to discover that he’s wearing large underpants beneath it. He takes them to the Khasi, who sees the possibility and, sure enough, it soon escalates to the point where he can convince the Burpas that there is nothing to fear from men who wear such garments under their skirts and a native uprising begins.

This set-up is perfect for a

Carry On film and it’s aided by a host of fortuitous circumstances, because budgets were never high for

Carry On films. This one cost a mere £260,000, even with a dozen or so regular cast members; even the biggest stars, like Kenneth Williams, were only paid £5,000 per film. Rogers planned

Carry On Dallas in 1980, a spoof of the TV show, but had to ditch the idea when Lorimar Productions wanted twenty times the entire production budget as their royalty fee.

Carry On Cleo was the greatest beneficiary of circumstance within the series, able to use expensive costumes and sets created and built for the Elizabeth Taylor version of

Cleopatra but abandoned when production moved to Rome. However

Carry On... Up the Khyber also lucked out, as all the kilts were re-used from the Alec Guinness film,

Tunes of Glory. The Governor’s Residence is Heatherden Hall, a Victorian country house located within the grounds of Pinewood Studios. The Khyber Pass scenes were shot on Mount Snowden in Wales.

Rothwell’s scripts were generally written with series regulars in mind for specific characters, which is why Roy Castle’s one and only appearance is in a role clearly intended for Jim Dale, but this one features what are arguably the best roles for many of those regulars. Sid James was top billed in 17 of his 19

Carry On appearances and Kenneth Williams was the most regular of the regulars, appearing in 25 of the 30 films, but these are quintessential roles for them. Beyond Bresslaw as Bungdit Din, I’d suggest that Joan Sims, Terry Scott and Peter Butterworth never got better roles either as the common-as-muck Lady Joan Ruff-Diamond, the gruff Sgt. Maj. MacNutt and the lecherous missionary, Brother Belcher, respectively. Other regulars, such as Charles Hawtrey, Angela Douglas and Julian Holloway, are also well cast and Cardew Robinson is perfect in his sole series appearance as an inept fakir. The consistent quality of these actors and Rothwell’s scripts are the two primary reasons why this series did so well.

And Rothwell was never better than here. Some jokes are truly awful but perfect for the moment, such as when Brother Belcher, horrendously disguised as a Burpa chief, carries on with a harem girl in a jewelled bra. ‘Are those rubies?’ he asks her. She replies, ‘No, they’re mine.’ When the British prepare to defend against the natives, Capt. Keene issues the command to fire at will. Brother Belcher comments, ‘Poor old Will! Why do they always fire at him?’ As the ceiling falls in on Lady Joan during the native uprising, she laughs it off. ‘Oh dear, I seem to have got a little plastered!’ Some are mildly rude, such as an exchange in which the Governor politely receives the Khasi’s compliments with succinct responses, which lead to, ‘And may his radiance light up your life!’ ‘And up yours!’ Many are dirty jokes indeed, like one during the introductory conversation at the polo match. Talking about the Khasi, Sir Sidney tells his wife, ‘I wouldn’t trust him an inch,’ to which she saucily replies, ‘Neither would I.’

Some jokes are situational, such as when Private Widdle paints a thin red line across the courtyard of the Governor’s Residence, a reference to the Battle of Balaclava when a thin line of red shirted Highlanders scared off a Russian cavalry attack, ‘the thin red line’ becoming a symbol of British stiff upper lip. Having the Khyber Pass, ‘the gateway to India’, be a traditional British sheep gate with ‘Please shut the gate’ on it, is priceless. More topically, the Khasi is dismissive when one of his men announces the arrival of Sir Sidney by sounding a gong, uttering the line, ‘Rank stupidity!’ This film was distributed by the Rank Organisation, whose ident is a similarly dresed man sounding a gong. Ultimately it all comes down to the final scene, when Sir Sidney and his officers ask the ladies if they can leave the dinner table, after the natives finally breach their gate. They saunter outside to the battle and treat the whole thing as a polite game. ‘Permission to have a bash, sir?’ asks Maj. Shorthouse, before leaping into the fray.

These final scenes are the

Carry On series in microcosm. We British are always good at laughing at ourselves and that pervades the history of our humour. It was a rare

Carry On film that didn’t target a traditional British institution, from Hammer Horror films to the National Health Service, from caravan holidays to Brits abroad, from the armed forces to the trade unions. The British Empire was a logical target, but it allowed Rothwell to really hone in on what it meant to be British. These final scenes both celebrate and lampoon the heart of the British mindset. We’re brave, we’re cultured and we’re cool under pressure, but we stand on ceremony, we make a ritual out of everything and we take things to ridiculous extremes. I can’t say that this movie is perfect: not every joke hits, there are slow bits throughout the middle and the plot could have been tighter. However, as a proud Briton who wears a kilt every day, this is part of who I am. It’s an institution in itself, just like the entire

Carry On series.